Higher Education in Reentry Reimagined

How can formerly incarcerated people living in New York City be connected to long-term higher education upon release from prison?

Partners & Funders

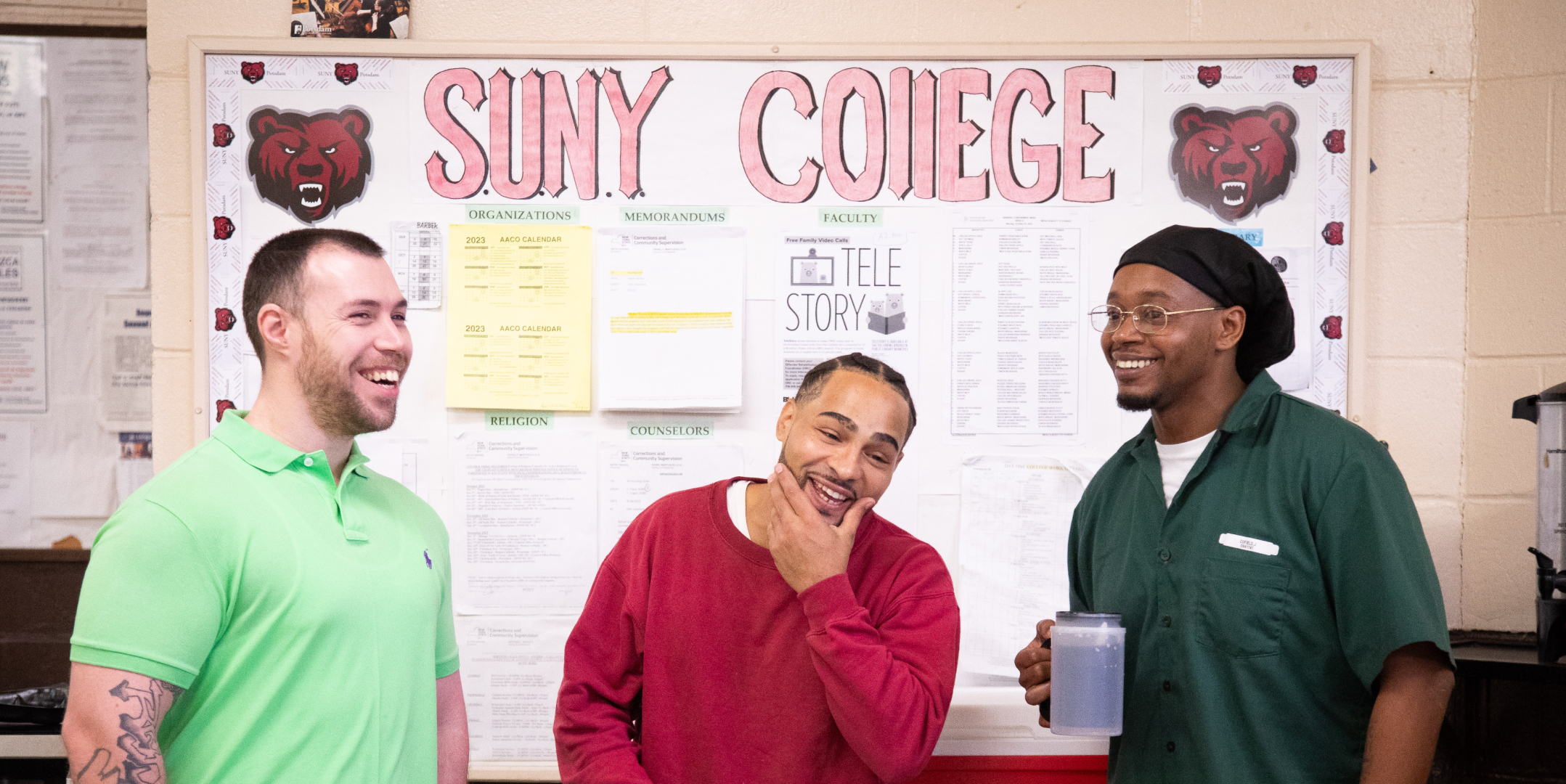

Photo credit: Valerie Caviness / The State University of New York.

The Project

The State University of New York (SUNY) is committed to providing educational equity for incarcerated New Yorkers. However, connecting people to higher education opportunities upon release remains challenging. We’re working with university systems in New York City and the state to improve access to quality education for students post release and build more pathways from prison to college.

The Outcome

Over six months, we will create tools and materials to strengthen the collaboration between the SUNY and CUNY systems, as well as CBOs and other stakeholders, to streamline pathways for reentry into college for those released from prison.

Higher Education in Reentry Reimagined

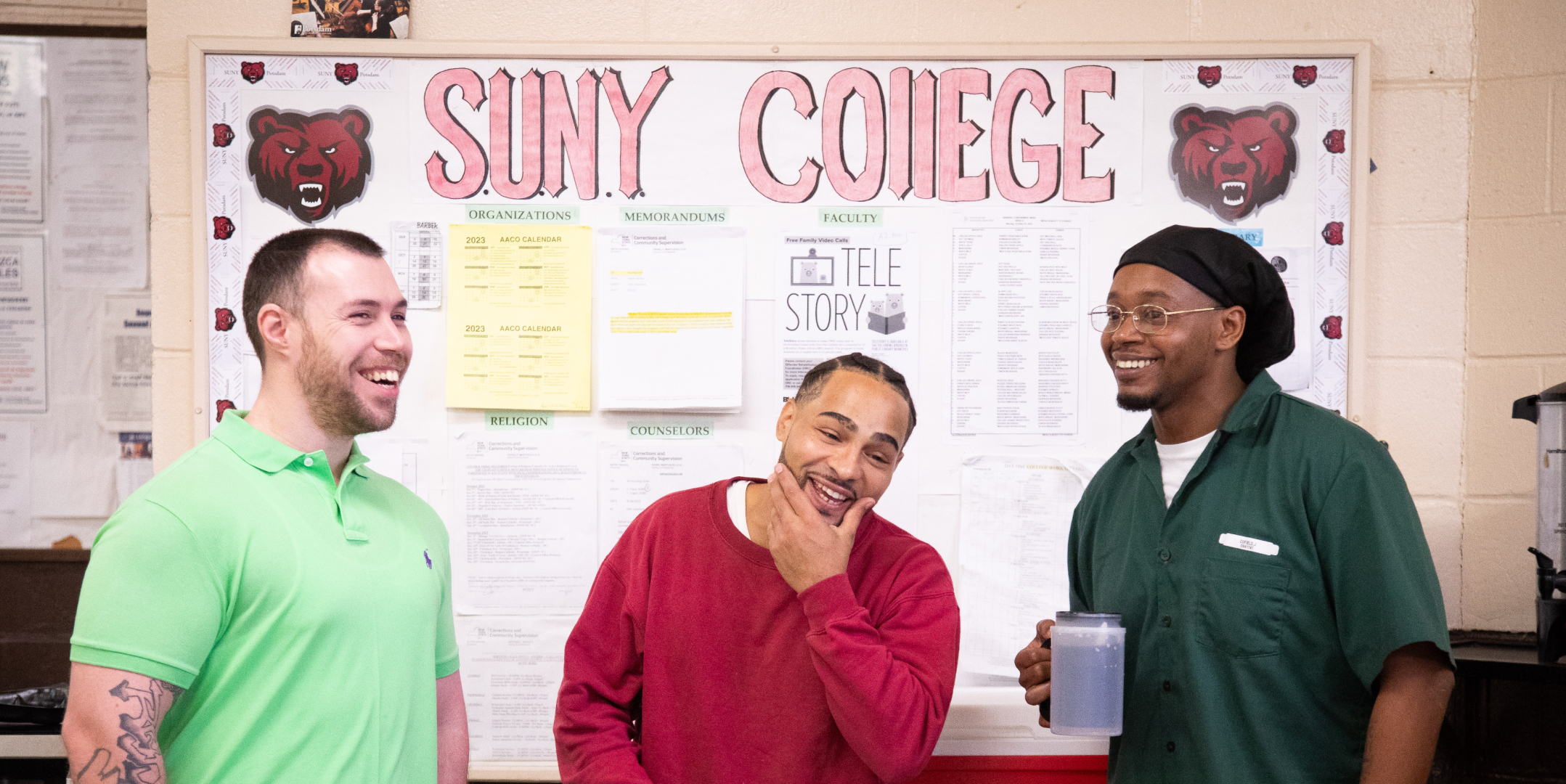

Photo credit: Valerie Caviness / The State University of New York.

How can formerly incarcerated people living in New York City be connected to long-term higher education upon release from prison?

Partners & Funders

The Project

The State University of New York (SUNY) is committed to providing educational equity for incarcerated New Yorkers. However, connecting people to higher education opportunities upon release remains challenging. We’re working with university systems in New York City and the state to improve access to quality education for students post release and build more pathways from prison to college.

The Outcome

Over six months, we will create tools and materials to strengthen the collaboration between the SUNY and CUNY systems, as well as CBOs and other stakeholders, to streamline pathways for reentry into college for those released from prison.